Undernourished and overlooked: addressing the silent epidemic of malnutrition

Malnutrition is a silent epidemic in hospitals—often overlooked, frequently underdiagnosed, and deeply consequential.1 Malnutrition, specifically undernutrition, is a lack of nutrients needed for a person’s health caused by impaired absorption, inadequate intake, increased nutrient needs, or altered nutrient transport and use.2

While the image of malnutrition can conjure thoughts of famine or food insecurity, it’s a clinical condition that affects an alarming number of patients with estimates suggesting that 1 in 3 are at risk.3 Some estimates say up to 60% of patients are malnourished.4 In critically ill patients, the risk can be even greater due to inflammation and altered metabolism.4,5

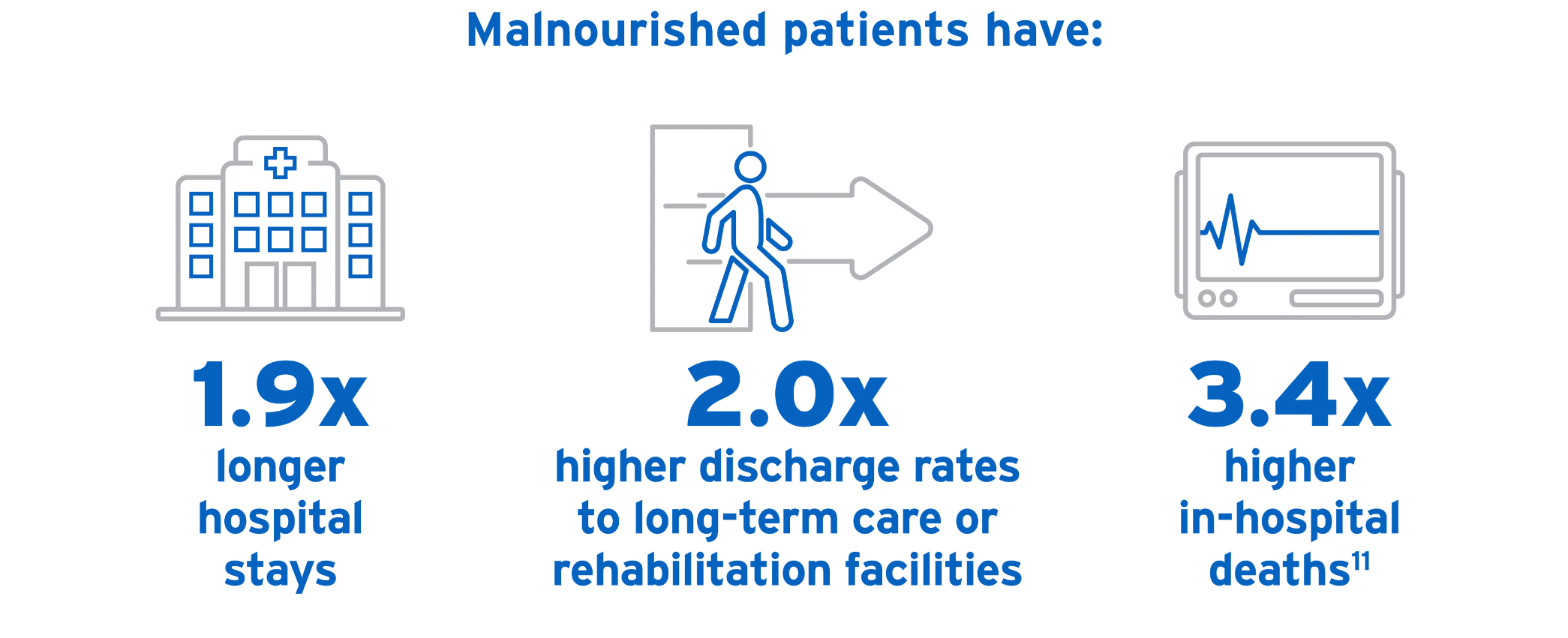

Left unaddressed, malnutrition may lead to increased length of hospital stay, higher healthcare costs, and greater morbidity and mortality rates.6-9 Through understanding how malnutrition is defined and diagnosed, clinicians can ethically and effectively address it.

Defining malnutrition

In adults, malnutrition can take several forms, including:

- Starvation-related malnutrition, such as from anorexia nervosa

- Chronic disease-related malnutrition, such as from organ failure or pancreatic cancer

- Acute disease or injury-related malnutrition, such as from burns, trauma, or major infection10

During illness, nutrition intake is critical in supporting body functions involved in recovery. In fact, up to 80% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients may be malnourished, which increases ICU length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, increases readmission rates to the hospital, and have up to 6.5x more cost compared to general ward patients.5

Malnutrition diagnosis: criteria and importance

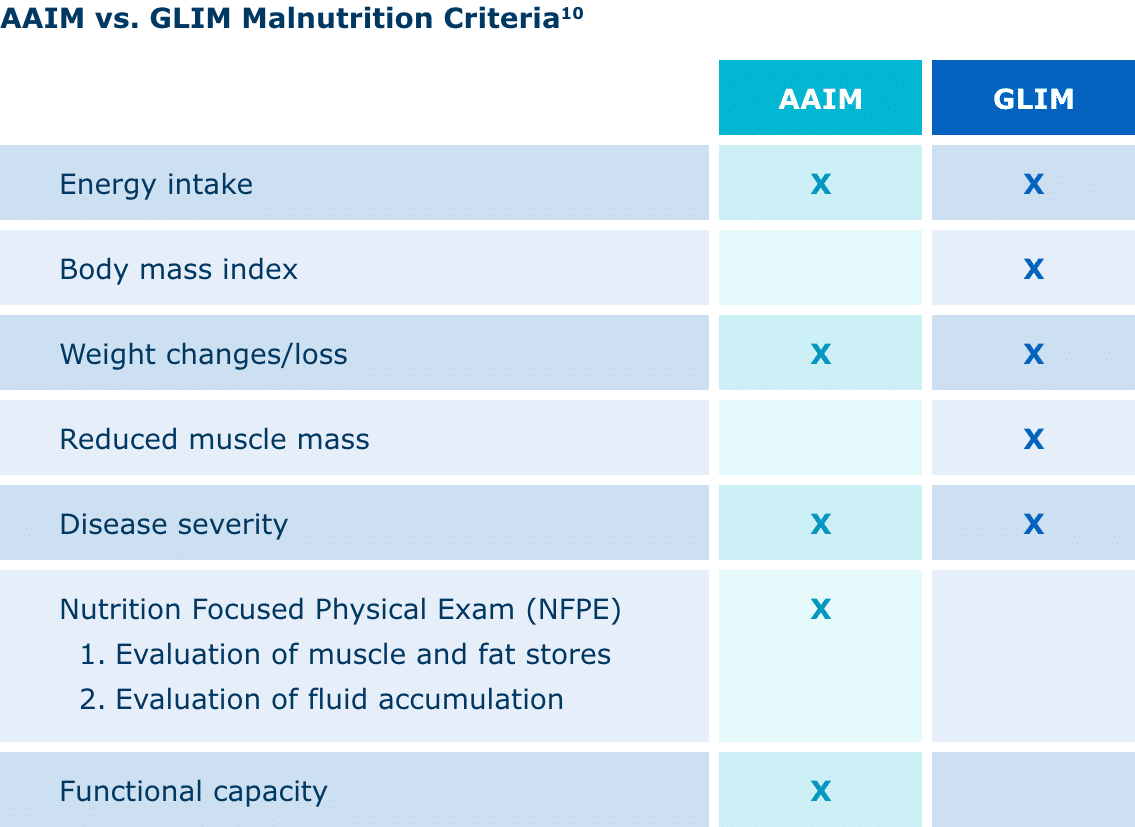

Currently, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Indicators to Diagnose Malnutrition (AAIM) and the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) both have distinct frameworks for diagnosing malnutrition.

AAIM assesses factors such as weight loss, energy intake, fat and muscle loss, edema, and hand grip strength. It’s been shown to have predictive validity for patient outcomes. GLIM is designed as a global consensus on criteria, allowing for global comparisons of malnutrition prevalence, treatments, and outcomes.10

Diagnosing and treating malnutrition in a timely and effective manner is directly related to clinical outcomes. Malnutrition can increase length of stay, hospital costs, and readmission rates. It can also contribute to poor wound healing and recovery.5

Because malnutrition often goes unnoticed, a universal set of diagnostic criteria is critical. Not only will this help healthcare providers recognize malnutrition, contributing to more accurate estimates of its prevalence, but it will also help guide best practices and inform expected outcomes. Even more, it will help predict and mitigate the financial burdens of malnutrition’s prevention and treatment.4

Using parenteral nutrition to address nutritional gaps in hospitalized patients

Parenteral nutrition or PN has proven efficacy in helping hospitalized patients meet nutritional goals.12 After a full evaluation and ruling out the feasibility of enteral nutrition, PN should be used for patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnourishment.13

ASPEN’s guide to PN11:

- Don’t use PN based only on medical diagnosis or disease state.

- Before initiating PN, conduct a complete evaluation of the feasibility of enteral nutrition (EN), using medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic evaluations.

- After ruling out EN, use PN in patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnourishment.

- Begin PN:

- After 7 days for well-nourished, stable adult patients who haven’t been able to receive 50% or more oral or enteral nutrients.

- Within 3 to 5 days for patients who are nutritionally at risk and aren’t likely to achieve desired oral intake or EN.

- As soon as is feasible for patients with baseline moderate or severe malnutrition and insufficient or impossible oral intake or PN.

- Delay PN in patients who have severe metabolic instability until they are improved.

As part of a nutrition care plan, including PN, multi-oils and alternative lipid injectable emulsions (ILEs) should be considered.

PN is not without risks, with the primary concern being infection of the bloodstream.14

Still, PN is a critical tool in nutritional care for malnourished or high-risk patients, and the benefits far outweigh the risks in giving patients a chance to heal and recover. For many patients, PN can be lifesaving.

Moving forward in clinical nutrition

Malnutrition is prevalent and serious—but it can be treatable. Clinicians must assess, diagnose, and act quickly, using standardized criteria and following best practice guidelines to improve the nutritional status and outcomes of patients.